In conversation with our communications officer, Nalé Barbieri Pederiva, Kleinsy Bonilla – Guatemalan diaspora expert co-leading the CDL project “Engaging Guatemalan Scientific and Professional Diaspora” – reflects on the challenges faced and how diaspora and public institutions are working together to promote national development.

“We all have migrant relatives,” begins Kleinsy Bonilla. “In Guatemala, as a society, we are marked by migration. A significant number of Guatemalans have migrated to the United States as an economic migration destination, and this has an imprint in all our families. I knew about this deeply rooted phenomenon, but this other migration—that in which highly educated and qualified Guatemalans develop professional and research activities abroad—is to a certain extent invisible, understudied and underreported. I have personally experienced this type of international mobility since the mid-2000s and in fact have pursued it as a research interest since 2009.”

Kleinsy‘s story highlights a broader opportunity for Guatemala: through the National Secretary on Science and Technology (SENACYT in Spanish) and the Academy of Sciences of Guatemala, the country has partnered with EUDiF since last year under the CDL project “Engaging Guatemalan Scientific and Professional Diaspora”. Together with an implementing team of 16 diaspora experts, we are working on strengthening the collaboration between diaspora professionals and national institutions to ensure systematic ways in which diaspora members can contribute to Guatemala’s development.

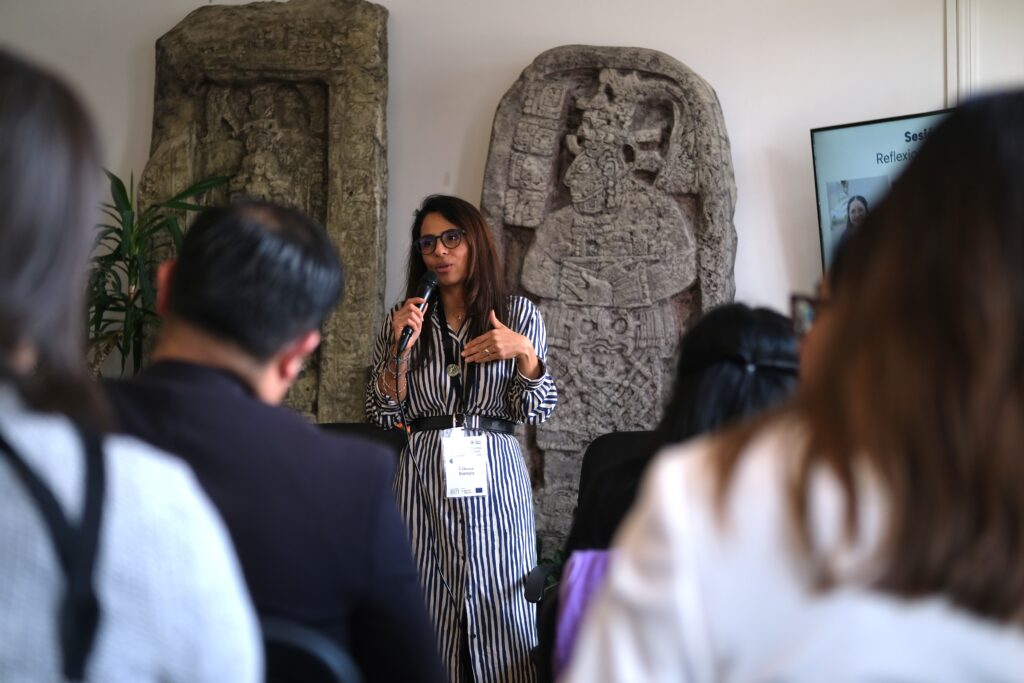

Central to the project are consultations with academic and public institutions, as well as with scientific and professional diaspora communities, based both in the United States and in Europe. Hybrid consultations and in-person workshops were organised throughout the second half of last year with representatives from key government entities and universities to improve inter-institutional dialogue and align efforts.

On the diaspora side, last November (2025), over 50 Guatemalan scientists and professionals living in the United States of America participated in a virtual focus group. Meanwhile, their Europe-based counterparts gathered for the first time in February (2026) at the Guatemalan Embassy in Paris for an in-person discussion on the contextual factors impacting diaspora engagement in Guatemala, the participants’ experiences and possible avenues forward in terms of diaspora visibility and connection. In addition, over 200 diaspora members completed the first general survey targeting specific groups of the GSPD residing in USA and Europe.

The results of these activities are being analysed, summarised and will inform the project’s final policy recommendations to SENACYT and more broadly to the Guatemalan relevant institutions. However, the conversations highlighted the need for more structured and sustainable spaces where the scientific diaspora community can share expertise and knowledge and the commitment to provide recommendations on development solutions in Guatemala and inspire young people to pursue scientific careers, through rural school visits for instance.

Reflecting on the discussions that took place in Paris, Kleinsy Bonilla shared how her story intertwines with the project, the main challenges ahead and why this initiative presents a unique window of opportunity.

Nalé Barbieri Pederiva: Could you tell us a bit about your professional journey?

Kleinsy Bonilla: I am from a town in Guatemala called Jalapa. My first migration was when I moved to the capital city at 16. That is when I began to think about mobility, but it took me several years to see myself as a migrant and as part of the diaspora.

When I was 26, I left Guatemala for South Korea to pursue a master’s degree. There, I began to seek knowledge about development and to understand why Guatemala experienced extreme wealth alongside extreme poverty. If I wanted to find explanations, my initial degree in law was not enough, so I studied public policy and socio-economic development.

Later, I moved for four years to Santiago de Chile, where I deepened my interest in student mobility, especially in the formation of Guatemalan human capital, frequently supported through international cooperation scholarships. This interest remained during my four years living in Brazil, where I pursued further research initiatives related to international cooperation in science and technology in lagging countries such as Guatemala and Central America. In 2022, I received an invitation to move to Norway, always remaining connected to Latin America, as my work focuses on preserving tropical forests, especially in the South American Amazon.

There is another element that has also shaped my research interests and professional development: the participation of women in higher education and in science and technology in these contexts.

NBP: Was that permanent connection with Guatemala what motivated you to participate in the EUDiF project?

KB: Absolutely! During those years I mentioned, I participated in various research networks and collaborated with colleagues residing in Guatemala, Central America and across Latin America. There are three that stand out: the Institute for the Development of Higher Education in Guatemala (INDESGUA); the Organisation for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD), Guatemala chapter; and the Network of Science, Technology, and Innovation of Guatemala. It has been 19 years now, but these collaborations and joint work processes have not been interrupted.

NBP: Given those almost 2 decades of collaboration, what persistent problem do you think this project addresses?

KB: Challenging the “brain drain” paradigm. That idea that we disappear from the planet or that our country of origin loses us. We have identified multiple ways to generate win-win spaces, where we, the diaspora, win, and the country also wins. We mobilise resources, gain access to world-class research facilities in our countries of destination and continue collaborations with peers who remain in Guatemala. Moreover, we engage in consulting, advising and mentoring with impact in the country.

We managed to form a team of 16 experts, bringing together colleagues based in Guatemala and abroad to implement the project. This creates and promotes synergy in our work. On the one hand, those of us in the diaspora have, or have had, access to good practices internationally. On the other hand, those in the country know the day-to-day and can implement at the local level. That local presence has enabled inter-institutional communication and allowed the project to move forward.

I would also like to recognise the institutional vision promoted by SENACYT and its authorities, as well as the Guatemalan Academy of Sciences, because without that step forward and that trust, it would not have been possible to establish this space.

NBP: Given that the will is there, what institutional challenges does Guatemala face in engaging its diaspora?

KB: The Guatemalan institutional context is fragile. We have a young democracy, which has had an impact on the stability of institutions and has delayed the building of trust.

However, within this difficulty there is also strength. Thanks to the work that SENACYT has been doing, for example, through Converciencia, which is an annual event celebrated since 2005 and has been one of the few spaces where we, the Guatemalan diaspora, have collaborated with those residing in the country. This has happened over the last 20 years despite changes in administration.

Scientific networks have also been quite stable. For example, the RedCTi network reached two decades of continuous operation this year. I have been following this type of institutional work for quite some time, and we had not found a window of opportunity like the one we have from 2023 onwards, where many key institutional actors came together, including the leadership of SENACYT and the Guatemalan Academy of Sciences, which acted as the glue uniting us.

NBP: And on the diaspora side, what challenges have been raised the most in the focus groups?

KB: We need to overcome scepticism and build trust, because the diaspora members have been struggling to be heard, to participate, and to be considered as a valid actor, as individual efforts though. Through this project, we have identified that collective efforts are more effective. Until now, many collaborations and participations have occurred episodically, in isolation or without the systematisation and scale required to generate deeper impact in our country of origin.

This project is making it possible for more voices from the diaspora to join. There are colleagues who have reached a level of prominence in their destination countries who have been collaborating with Guatemala, but in an episodic or atomised way. Now they are uniting efforts and therefore enabling us to scale up our impact.

At the same time, within Guatemala, there were also spaces that were not articulated. Now we are recognising one another, and inter-institutional dialogue is extremely valuable.

In this project we have also heard some alarm bells telling us: “If the diaspora gains visibility, we are going to generate more brain drain.” And that is the challenge for us: changing that paradigm. We migrate for many different reasons, we establish our residency elsewhere and intend to remain living abroad, and yet we remain relevant and a potential asset for Guatemala

NBP: What would be your message to the diaspora?

KB: The message is to join the process, to identify in this an opportunity for our voices to be heard more clearly, to be more decisive and impactful in our contributions, there are many ways each diaspora member can interact with us and move from an individual to a collective approach. For those who want to and who have an interest in continuing to collaborate with Guatemala, to seek us out. We will respond, connect and engage.

In the meantime, we are strengthening coordination among ourselves. That is part of the legacy of this project, because we are not only strengthening our relationship with our country of origin, our collaborations, but also deepening collaboration among ourselves in the different spaces where we work. We are building spaces for mutual growth and support in our countries of residency. So, the message is: let’s seek and find each other.

Contact: diasporaguatemala@senacyt.gob.gt